Wabi-Sabi

The Natural Beauty of Japanese Tableware

Japanese aesthetics, born from the spirit of "mono no aware" as seen in The Tale of Genji, and

intertwined with concepts like "yugen" (subtle profundity) and "wabi-sabi" (beauty in

imperfection), is deeply embedded in their tableware.

This beauty manifests in the way these vessels retain the marks of the maker’s hand, embracing

simplicity and avoiding unnecessary adornment. Even when worn or imperfect, these items are

cherished for their unique appeal. The asymmetry of Japanese ceramics is a direct expression of this

"natural beauty," preserving the raw textures and simple, organic patterns that embody an

unpretentious harmony.

Ceramics

The fractures, wear, and stains that develop on these ceramics through daily use form a connection

between the user and the vessel, imbuing it with a life-affirming natural beauty. Even when

repaired, the imperfections are preserved as part of the object’s narrative.

Across Japan’s 47 prefectures, each region produces distinct ceramic wares, often named after their

place of origin, such as "Imari-yaki," "Karatsu-yaki," and "Mino-yaki."

Kiyomizu-yaki

Named after Kyoto’s ancient Kiyomizu Temple, is renowned as a representative of

"Kyo-yaki." This form of pottery, perfected by Nonomura Ninsei in the mid-17th century, is

celebrated for its delicate painting and vibrant glazes. The intricate designs and varied techniques

make Kiyomizu-yaki a national treasure of Japan.

Mino-yaki

with a 1300-year history from the Tono region of Gifu Prefecture, is known for its

vibrant underglaze decoration. Fired at high temperatures of 1200-1300°C, the glazes fuse with the

clay body, producing a glossy, luminous surface. The irregularities in thickness, curvature, and form

give Mino-yaki its distinctive asymmetrical beauty, capturing the essence of freedom in

imperfection

Lacquerware

Lacquerware, a unique craft of the East, flourished in countries like Japan, China, Korea, and

Southeast Asia. Among them, Japanese lacquerware gained global fame early on, so much so that

"Japan" became synonymous with lacquerware.For Japan, lacquer is a familiar and significant presence, with its use tracing back over 2,500 years

to the Jomon period. Lacquerware has woven itself into the fabric of Japanese life, serving as both

functional tableware and as decorative elements in architecture. Two representative decorative

techniques that have survived to this day are raden and maki-e.

Raden

Involves embedding thin, iridescent slices of shell, such as abalone or pearl oyster, into the

lacquer layers, creating luminous designs. The plum blossoms in the image below showcase this

technique, their vibrant hues crafted with intricate precision.

Maki-e

Is a technique where delicate patterns are drawn on the lacquer surface and embellished

with gold, silver, or other colors. The term "maki" originally referred to the sprinkling of gold or

silver powder, but today it also includes methods like inlaying metal foils. The lacquerware in the

above image, a fine example of Kanazawa lacquerware, is adorned primarily with maki-e, except

for the raden details.

Ochi-me

The outline pattern used in maki-e, is traced onto the thin Mino paper template, and then

lacquer is applied from the reverse side. The design is transferred onto the surface of the object,

dusted with a shell-based pigment called gofun, making the outline visible. Typically, these outlines

remain unseen by the observer.

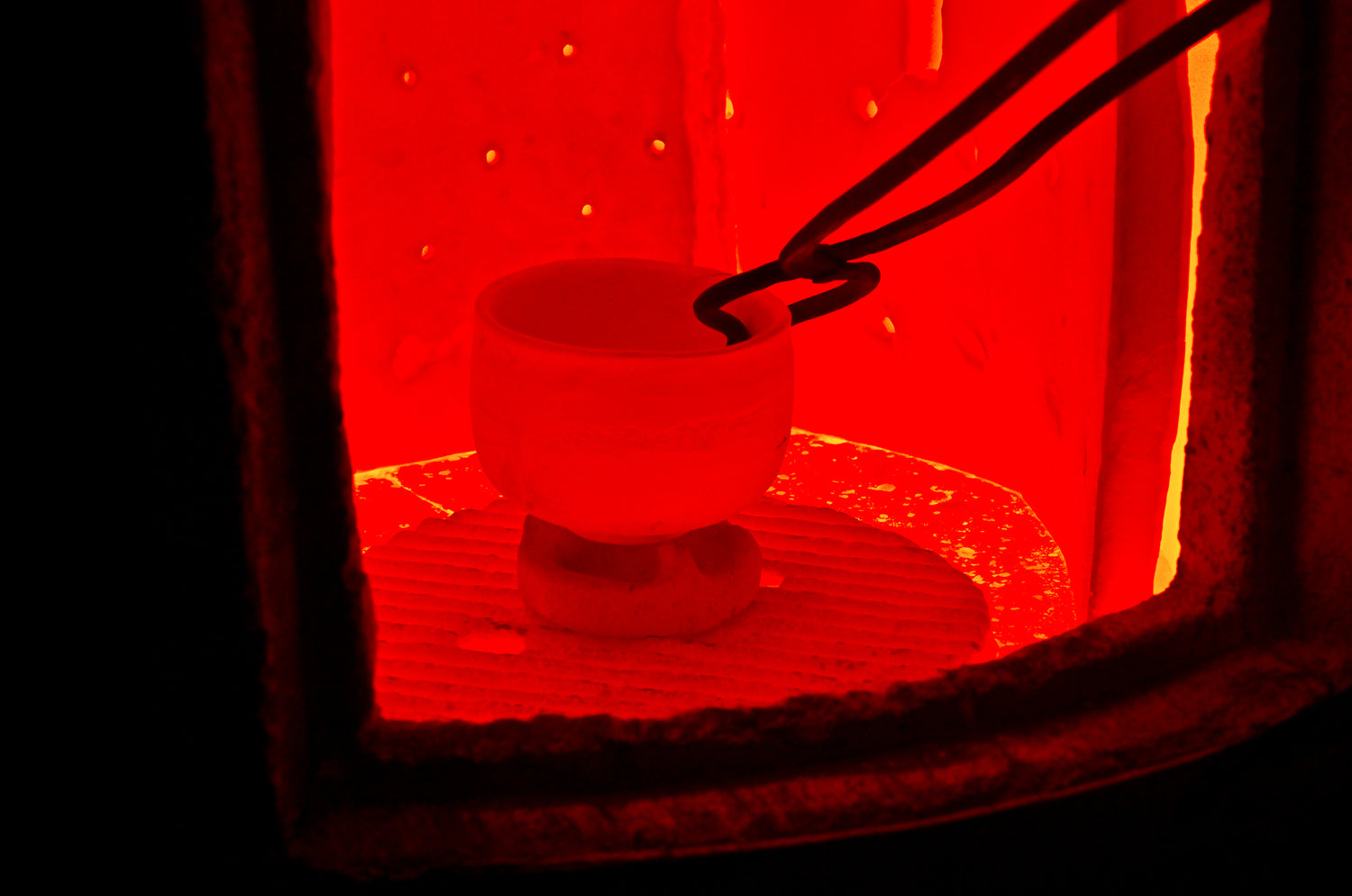

Ironware

Nambu ironware refers to the cast iron craftsmanship originating from the cities of Morioka and

Oshu in Japan’s Iwate Prefecture. These ironworks, known as Nambu ironware, are crafted from

natural iron, embodying a cycle of creation and return to nature. As household items, Nambu

ironware has been preserved for over 400 years, growing richer in texture and character with use,

each piece developing a unique patina influenced by its owner.

The most famous of these is the Nambu iron kettle, used for brewing tea. These kettles come in

various shapes, such as round, flat-bottomed ovals, and the natsume-maru, with traditional motifs

like cherry blossoms, chrysanthemums, peonies, pines, and auspicious animals such as horses and

turtles adorning their surfaces. Each kettle undergoes approximately 65 steps in its creation, most of

which are completed by hand. Becoming a craftsman takes at least 15 years, with each believing

that they must create with a user in mind, a belief passed down over 400 years.

The intricate process of making Nambu ironware begins with sketching the design, followed by

mold making, creating the clay mold, and then firing it. The molten iron is poured into the mold,

and once the basic form is achieved, the kettle is heated to 800-1000°C using charcoal to create a

protective film on its surface to prevent rusting. The entire process, with all its meticulous details,

can take nearly two months to complete a single piece.